EHR-Xamine

A Virtual Assistant for Electronic Clinical Health Records

Introduction

In the world of healthcare, physicians are required to work with rapidly growing amounts of medical data. The National Physician Poll by The Harris Poll in 2018 reports that 71% of physicians believe Electronic Health Records (EHR) greatly contribute to physician burnout, and 59% of physicians think EHRs need a complete overhaul. Indeed, in the current status quo, approximately 62% of time per patient is devoted to reviewing electronic health records (EHRs), with clinical data review being the most time-consuming portion of it all. Records are often filled with duplicated, outdated and even unrelated data, let alone ordered in a chronological or logical order given the concerns of a patient. Sifting through an unoptimized package is not only tedious on a physician’s standpoint, but also forces them to spend unneeded time that could otherwise be spent directly talking to and understanding a patient’s current condition.

EHR-Xamine not only provides concise summaries of the patient and all packets within the pdf, but is further attached with a web-based user interface that answers questions regarding a physician’s health condition with complete explainability for its answers. To evaluate the potential time savings during for this aspect of our model, we compared the ability for our model to answer 23 clinically relevant questions to physicians’ ability to complete the same task on a non-chatbot version of our software. Our experiments show that there is no significant difference in question-answering accuracy compared to Chi et al.’s work, especially when it came to content-retrieval questions [83.8% (95% CI, 73.8 - 91.1%) vs 83.7% (95% CI, 79.3-88.2%)], while saving over 83% of time to reach the same conclusions.

Related Work

In recent years, there have been multiple attempts to design software to improve the physician experience. Park et al. [1] attempted to use natural language processing algorithms to search for information within medical documents. As part of Stanford ML Group, I worked alongside a team of Stanford engineers and clinicians to develop an artificial intelligence (AI) system developed to organize and display new patient referral records would improve a clinician’s ability to extract patient information compared with the current standard of care [2]. Using scanned pdf files, our software saved first-time physician users 18% of the time used to answer the clinical questions on average; furthermore, despite a learning curve pointed out by respondents, 11 of 12 physicians believed that the technology would save them time to assess new patient records and were interested in using this technology in their clinic.

While this research paper has made a lot of progress in the world of healthcare, a virtual assistant can further reduce the time spent on reading electronic health record documents. For starters, the system developed by Chi et al. does not identify the cause of the patient visit, which is an important feature in determining which lab results and past patient visits to prioritize. Furthermore, most chatbots in the healthcare sphere prioritize customer-facing chatbots, i.e. Ni et al. (2017) [3] developed a chatbot, "Mandy", that assists health care staff by automating the patient intake process. EHR-Xamine tackles this shortcoming in the product space by being a virtual assistant that extracts important information within a health record based on physician commands.

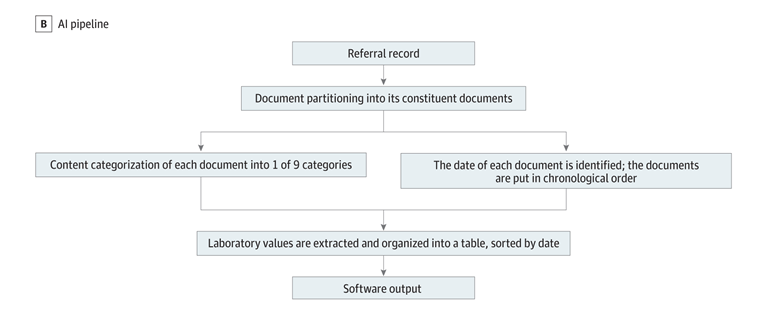

PDF Conversion Pipeline

This project uses the PDF conversion pipeline from Chi et al. as an important first step of the project. This pipeline begins with an (1) optical character recognition algorithm that reads text in PDFs to extract dates, laboratory findings and all other information, before (2) running a rule-based keyword label classification algorithm to sort all pages by content category (referral, fax, insurance, progress note, procedure note, radiology report, laboratory values, operative report, or pathology report). This pipeline is topped off with a (3) date extraction algorithm that identifies the most relevant date on each page in the record, followed by (4) a lab extraction algorithm that organizes the most relevant CBC (complete blood count) and other test results into a relevant table. Finally, (5) a page-grouping algorithm utilizes a convolutional neural network and textual heuristics to partition the record into its constituent documents. A more diagram of this pipeline can be seen below.

Figure 1: A diagram of the pipeline proposed by Chi et al. that converts a raw PDF clinical health record into an organized packet.

Virtual Assistants

Genie

Campagna et al. [4] propose an improvement in both the development methodology as well as the performance of virtual assistants. Their paper advocates for the use of a Virtual Assistant Programming Language (VAPL) to formalize the action space and capabilities of a virtual assistant, alongside a neural-based semantic parser that translates natural language commands into VAPL code. More specifically, they propose a toolkit, Genie, that only needs a small set of input sentences to validate the aforementioned semantic parser language model. Their paper reports that across multiple real-world tasks, Genie achieves a 62% accuracy on realistic user inputs and drives a 19% and 31% improvement over previous SotA on virtual assistants for music skill, aggregate functions and access control.

GPT-3

Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) is a large language model trained to predict a probabil- ity distribution over sequence of words. Alongside other similar projects released by OpenAI, i.e. ChatGPT, GPT-3 has attained state-of-the-art results across a multitude of NLP benchmarks and, in recent years, have been adapted to solve tasks in multiple different domains, from code completion and generation[5] to startups in the copywriting field [6]. Similar to its predecessor, GPT-3 utilizes a transformer-based architecture and is trained on roughly 500 billion tokens of textual data, with every 100 tokens representing roughly 75 words. On its publication date, GPT-3 was one of the largest language model ever released by parameter count: the first iteration of its largest model, davinci , contains over 175 billion parameters.Approach

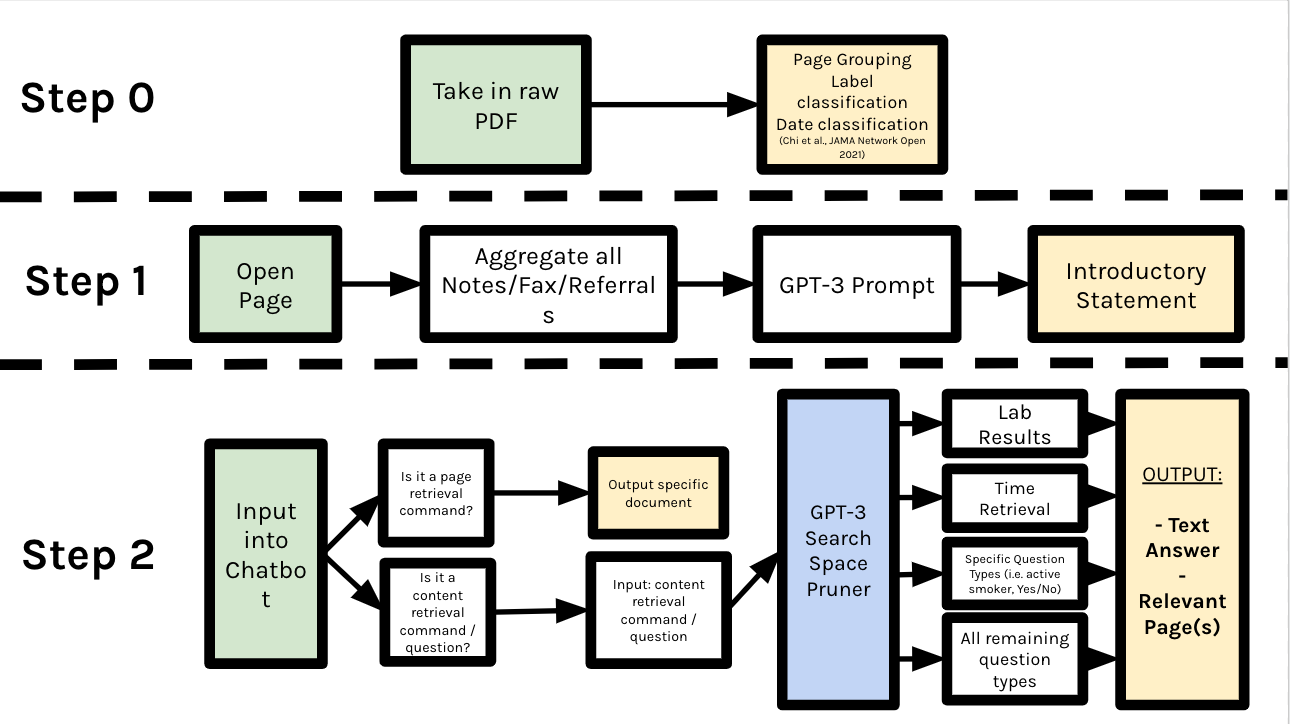

In this research, we investigate the use of large language models, specifically GPT-3, alongside traditional rule-based heuristics for extracting relevant information from unstructured data in raw electronic health record PDFs. First, raw PDFs often contain unstructured data, for which rule-based methods or virtual assistant programming languages, i.e. ThingTalk [4] will be less suitable for. Printed formats for note, referrals, labs...etc are wildly different across different hospitals and even across different years and clinics. More importantly, we propose a novel usage of GPT-3 as a search-space pruner in this paper. Since the usefulness of a information retrieval chatbot is directly correlated to its latency, we utilize clever prompt engineering to prune off irrelevant pages alongside rule-based heuristics. The pipeline of our virtual assistant can be seen below.

Figure 2: The entire procedure of the EHR-Xamine virtual assistant pipeline

Figure 2: The entire procedure of the EHR-Xamine virtual assistant pipeline

Step 0: Pre-Processing

As mentioned previously, the EHR-Xamine project utilizes the pipeline developed by Chi et al. to extract all lab results and convert a raw PDF into a list of packets, each with an accurate class and date label on it. Small improvements were made to the date classification algorithm to ensure that the model catches more potential dates, as well as the Cover Page Classifier to improve its accuracy from 88% to 91%. Our EHR-Xamine paper will then try to answer physician-prompted questions or commands by reading through the most relevant groups of information as constructed by our pipeline.

Step 1: Introductory Statement

Patient referrals serve as an important first document for physicians to understand the reason for a visit. Unfortunately, referrals are usually limited in their information coverage, as they may only include information from a specific patient visit and not a summarization of the greater patient condition. To tackle this shortcoming, our virtual assistant EHR-Xamine begins the dialogue with a physician by providing a three sentence summary of the patient’s condition.

For this part of the pipeline, we first begin by aggregating all notes, faxes and referrals in a PDF packet. Next, we feed all these summaries into the GPT-3 text-davinci-002 model alongside a summarization prompt:

Write a three-sentence summary of this patient given the following notes, in a way that will allow a new doctor to understand as much about the patient’s condition as possible.

Note n: [NOTE]

We set the temperature of the GPT-3 model to be 0.5, as we do not want the output format to deviate too much per packet, yet we do not want our outputs to become too formulaic.

Step 2: Page Retrieval Commands

Given an input into the chatbot, our EHR-Xamine pipeline first uses a rule-based methodology to determine whether the prompt is a page retrieval command (i.e. the physician wants to be redirected to a relevant page) or whether the prompt is a content retrieval command (i.e. the physician wants to know about a specific lab value or condition of a patient). Once our rule-based approach identifies specific starting keywords in the prompt, i.e. "Go to", "Summarize", or "Give an overview", we feed in the command into GPT-3 alongside a universal page retrieval prompt:

Which page is being referenced in the question? For context, here is a breakdown of the pages:

Page(s) [PAGES] (Category: [CATEGORY], Written on XX-XX-XXXX)...

EHR-Xamine then parses the very first number that appears in the GPT-3 output and redirects the user to the page. Here, we set the temperature of the GPT-3 model to be 0.1, as our model is no longer outputting a phrase of text that is being read by the physician. The GPT-3 response is immediately converted into a computerized action, and thus the output should follow a similar pattern each time.

Step 2: Content Retrieval Commands

As shown in the Pipeline diagram above on Figure 2, all non page-related packets are first run through a search space pruner to determine the best answer to a physician’s question or command.

GPT-3 Search Space Pruner

In this research, we investigate the use of a hybrid approach between rule-based and neural methods for search space pruning. We utilize GPT-3 to take in all non page-related prompts and output packet classes it thinks are relevant via the following prompt:

Which category types would you expect to find an answer to this question? There may be multiple correct categories! Below is a brief overview of the information contained in each category:

Referral: Contains a written order for a patient to see a specialist or get certain medical services. May contain information regarding patient’s insurance history as well.

Note: Contains all vital basic information on a patient, from their physical mea- surements and family background to their current medication and previous patient visits. This category is most useful for finding information regarding a patient’s general health condition.

Procedure: Contains information regarding an activity directed at or performed on an individual with the object of improving health, treating disease or injury, or making a diagnosis.

Radiology: Contains a report of a radiology. A radiology is a medical discipline that uses medical imaging to diagnose diseases and guide their treatment.

Lab: Contains ONLY numerical values of a test done in a laboratory for a patient. Any question that asks for a specific number is likely to be referenced here.

Operative Reports: This is report written in a patient’s medical record to document the details of a surgery. The operative report is dictated right after a surgical procedure and later transcribed into the patient’s record.

Pathology: Provides diagnostic information to patients and clinicians. It impacts nearly all aspects of patient care, from diagnosing cancer to managing chronic diseases through accurate laboratory testing.

Question: [QUESTION]

A regex parser then converts the GPT-3 suggestions into an array and appends it onto the rule-based keyword search. It is important to note that some rules in the rule-based keyword search have infinite weighting; for example, if the word "insurance" appears in the questions, all of GPT-3’s suggestions would be rejected.

The benefits of running a search space pruner are twofold: first, it saves a lot of runtime and credits that would otherwise be taken to parse through a completely irrelevant document, and; two, removing irrelevant pages would allow for EHR-Xamine to split a prompt into cleaner subtasks, resulting in much more accurate and relevant outputs over a wide variety of actions.

Overall, this approach allows us to leverage the power of large language models, such as GPT-3, while still maintaining the control and precision of rule-based systems. By combining these two approaches, we are able to improve the accuracy and efficiency of our search algorithm.

Lab Retrieval

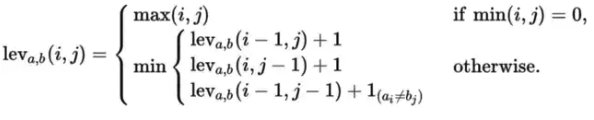

For all questions deemed a lab retrieval command by the search space pruner, we apply solely rule-based approaches to find the most relevant date and value. Since all lab values are aggregated on a table as part of the Chi et al. pipeline, it remains to search for the most relevant column. The most relevant column is determined by the smallest summation of the Levenshtein distance and the Jaro distance between the lab column and the query; the formula for Levenshtein can be seen in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: The equations for Levenshtein distance

Figure 3: The equations for Levenshtein distance

Date Retrieval

For all questions deemed a date retrieval command by the search space pruner, we again apply solely rule-based approaches to find the most relevant date. We use the date classification algorithm as proposed by Chi et al. to extract all possible dates from the relevant determined pages by the pruner, then choose either the most recent or earliest date as prompted by the physician.

Remaining Question Types

All remaining question types require us to look through unstructured data and, thus, require GPT-3 to lead physicians to the relevant answer and pages. For every question and every packet in the PDF that the search space pruner deems relevant, we feed GPT-3 with the below prompt:

Given the following context, please answer the question in as much detail as possible.

Context ([CATEGORY] published on [DATE]): [CONTEXT]

Question: [QUESTION]

with temperature 0.2, as we do not want large deviations in format.1 Once this is complete, we check if the question prompt follows a specific question type that could possibly require a different parsing technique. For yes/no questions, a BERT sentiment analysis model is combined with a bag-of-words model for keywords to determine the most relevant page and answer; a similar approach is applied for all smoking related questions. Otherwise, for questions that require EHR-Xamine to ’list’ an example, we feed all pages into GPT-3 and ask it to pick an example outputted across all the different pages. Finally, if the question is of an unseen type, we simply output GPT-3’s response across all potential packets of information. This is a design choice to help make our virtual assistant more interpretable when it is less certain about the answer or the question type.

User Interface

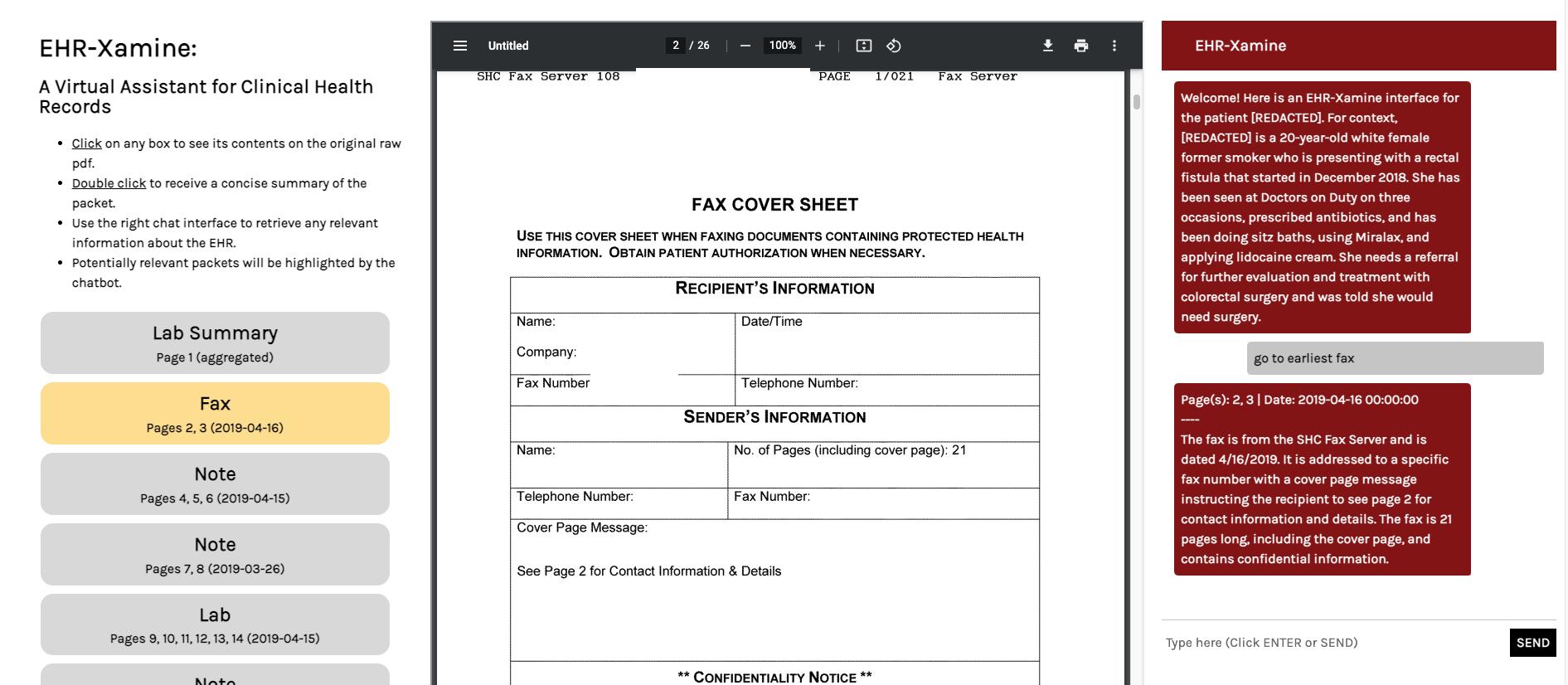

For EHR-Xamine to reach its fullest potential, we designed a user-friendly interface that would give physicians full control over their health record review, while ensuring that outputs by the virtual assistant are easily accessible and sanity checked, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: An image of the EHR-Xamine interface in action. Here, a page retrieval command is queried. Our virtual assistant highlights the relevant packet in the page of contents, redirects the physician to the relevant page and writes a summary of the fax.

Figure 4: An image of the EHR-Xamine interface in action. Here, a page retrieval command is queried. Our virtual assistant highlights the relevant packet in the page of contents, redirects the physician to the relevant page and writes a summary of the fax.

A hyperlinked table of contents of the packet is featured on the left third of the interface. Clicking on any packet will directly bring you to the relevant packet, and double clicking a packet will remove all highlighting and prompt EHR-Xamine to provide a concise summary of the packet. Meanwhile, the middle third of the interface contains an iframe for the raw pdf electronic health record, and works like a normal pdf viewer.

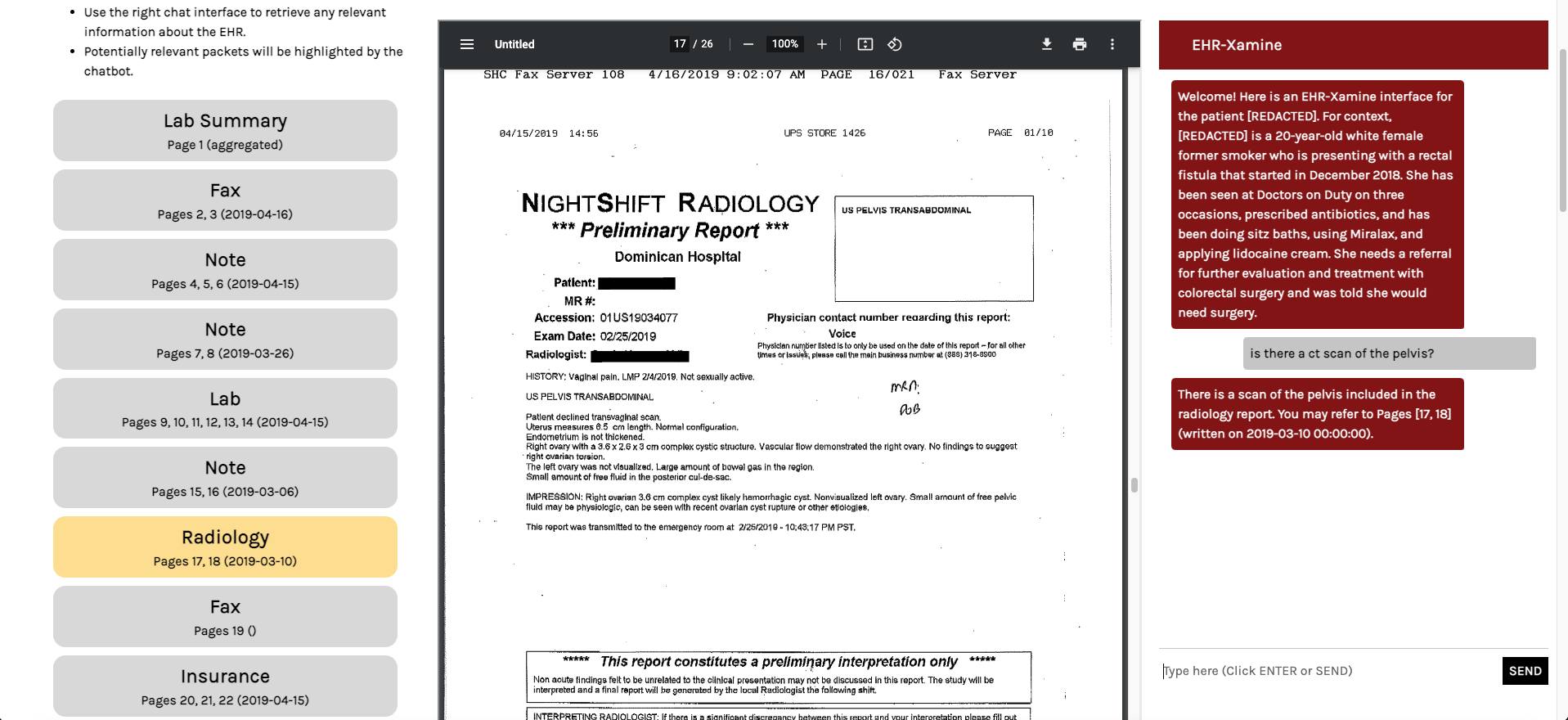

The right third of the interface allows us to read and write to the virtual assistant. If EHR-Xamine believes that the question has a searchable answer within the pdf, then the most relevant packets of information will be highlighted on the table of contents, as can be seen in Figure 4. Another example of this can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Another image of the EHR-Xamine interface in action. Here, a command retrieval command is queried. Our virtual assistant highlights the relevant packet in the page of contents, and redirects the physician to the relevant page.

Figure 5: Another image of the EHR-Xamine interface in action. Here, a command retrieval command is queried. Our virtual assistant highlights the relevant packet in the page of contents, and redirects the physician to the relevant page.

Experiments

Evaluation Metric

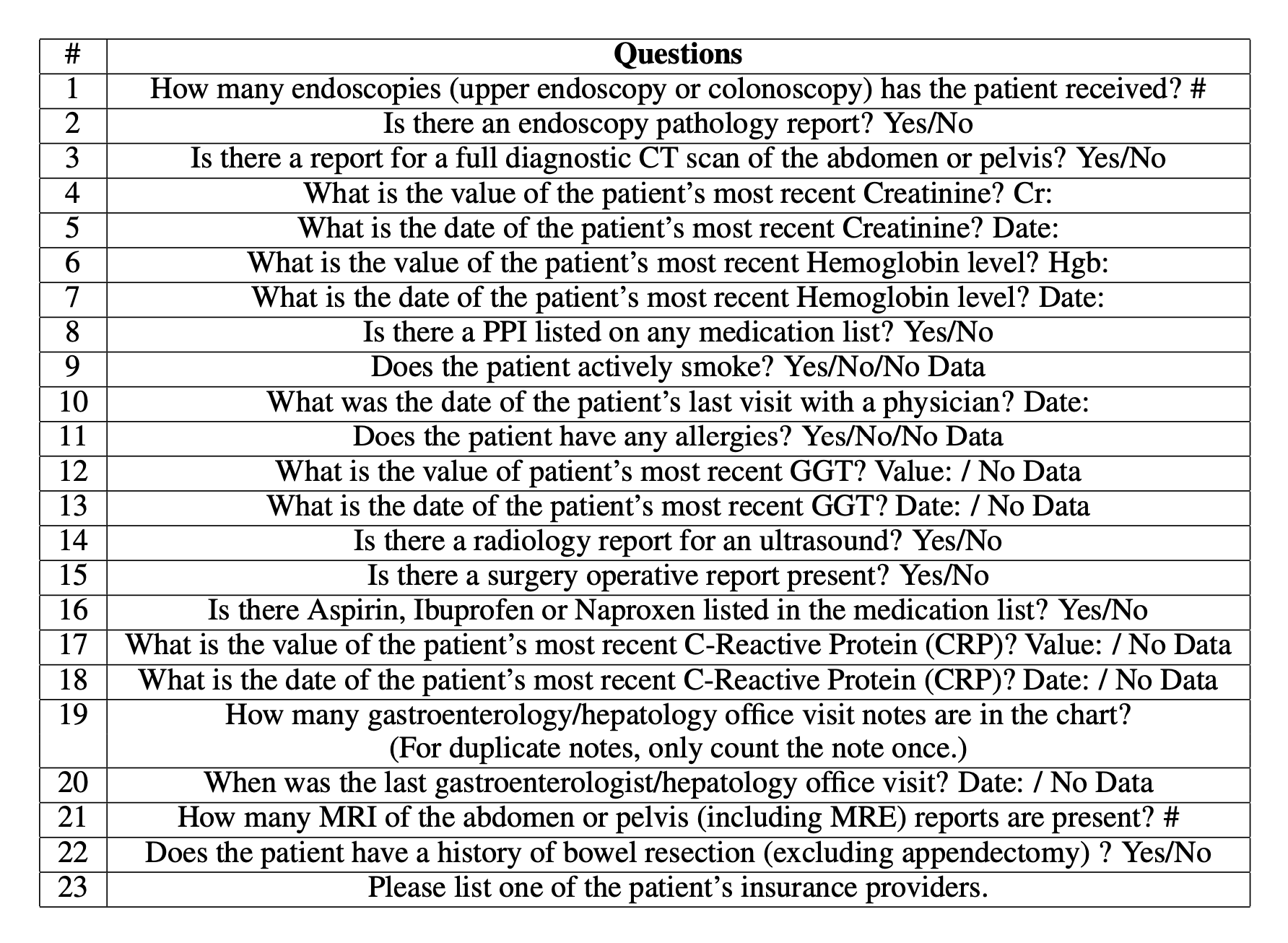

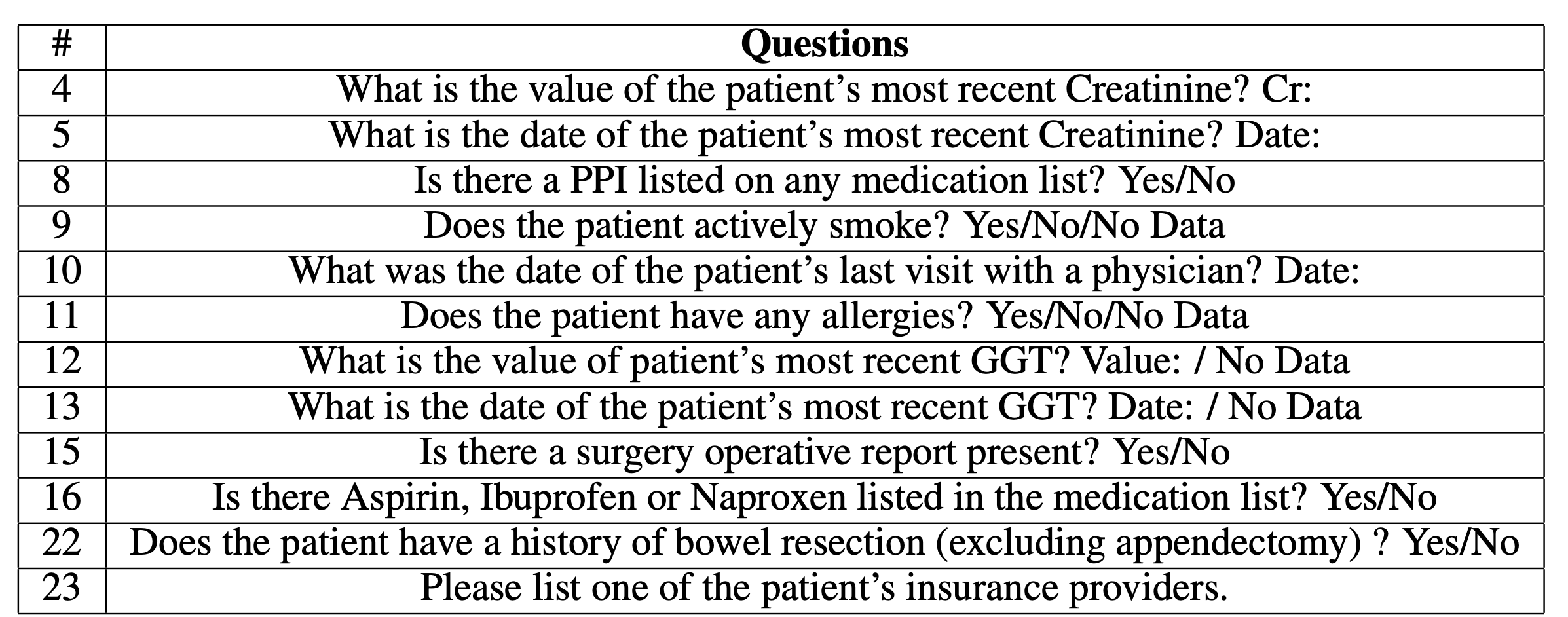

To evaluate the ability of EHR-Xamine to answer important healthcare questions across different domains, we ask our virtual assistant a total of 23 questions regarding a patient’s medical condition; we aim to compare the results from the baseline of the performance across twelve physicians with and without an AI assistant as reported by Chi et al [2]. The questions are as followed:

Data

As patient information is hard to request for for individual use, the EHR-Xamine system was developed as an add-on to the pipeline designed by Chi et. al and, thus, was developed using the same 45 patient referral records from the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Stanford University across a wide variety of gastroenterology clinicians. Across these patient referral records, four records are used for the evaluation of EHR-Xamine, for which ground truths of all above have been annotated for evaluation purposes.

Results

Accuracy

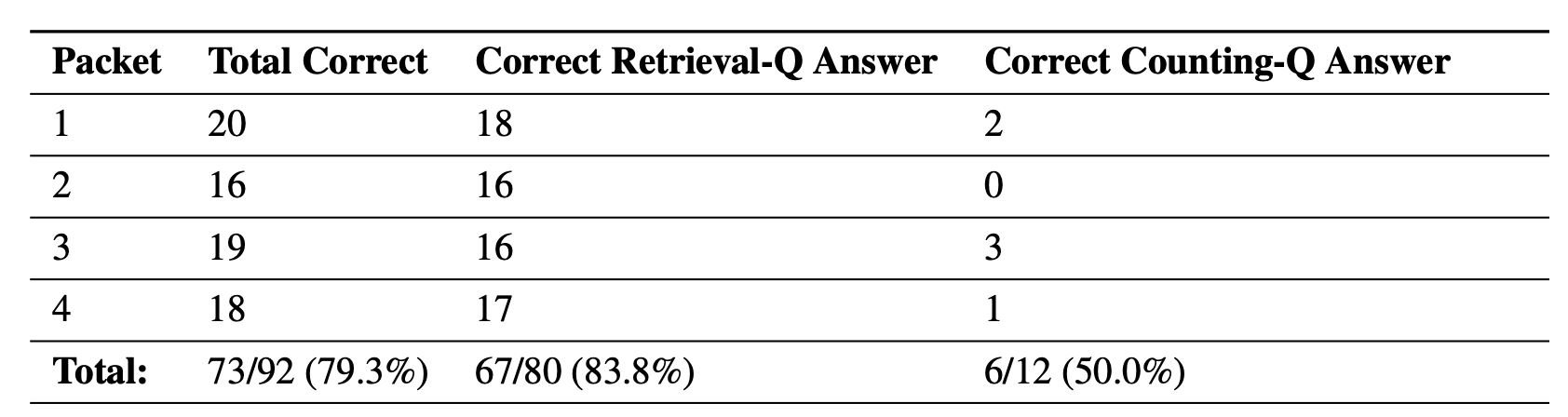

EHR-Xamine responded to the above questions with an accuracy of 79.3% (73/92) (95% CI, 69.6 - 87.1%) across 92 responses from 4 packets, compared to 83.7% (95% CI, 79.3 - 88.2%) by physicians with AI-assisted packets. Due to the small sample size of four packets, our main conclusion that our virtual assistant can perform the same task with no significant decrease in accuracy.

To further showcase the potential of EHR-Xamine in a clinical setting, we observe that our virtual assistant actually performs much better at retrieval questions (e.g. "Is there...?") compared to counting questions (e.g. "How many...?"), with an accuracy of 83.8% (67/80) (95% CI, 73.8 - 91.1%) for the former category but only 50.0% (6/12) (95% CI, 21.1 - 78.9%) for the latter. The former category is a lot more important for a physician, as it reduces the time taken to sift through a packet, while the latter requires a lot more inductive reasoning that a physician will have to do regardless of an assistant’s output. A deeper breakdown of this analysis across all packets can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: A breakdown of the accuracy of EHR-Xamine across different packet and question types. Here, we showcase that our virtual assistant is a lot more adept at answering retrieval based questions.

Table 1: A breakdown of the accuracy of EHR-Xamine across different packet and question types. Here, we showcase that our virtual assistant is a lot more adept at answering retrieval based questions.

Retrieval Speed

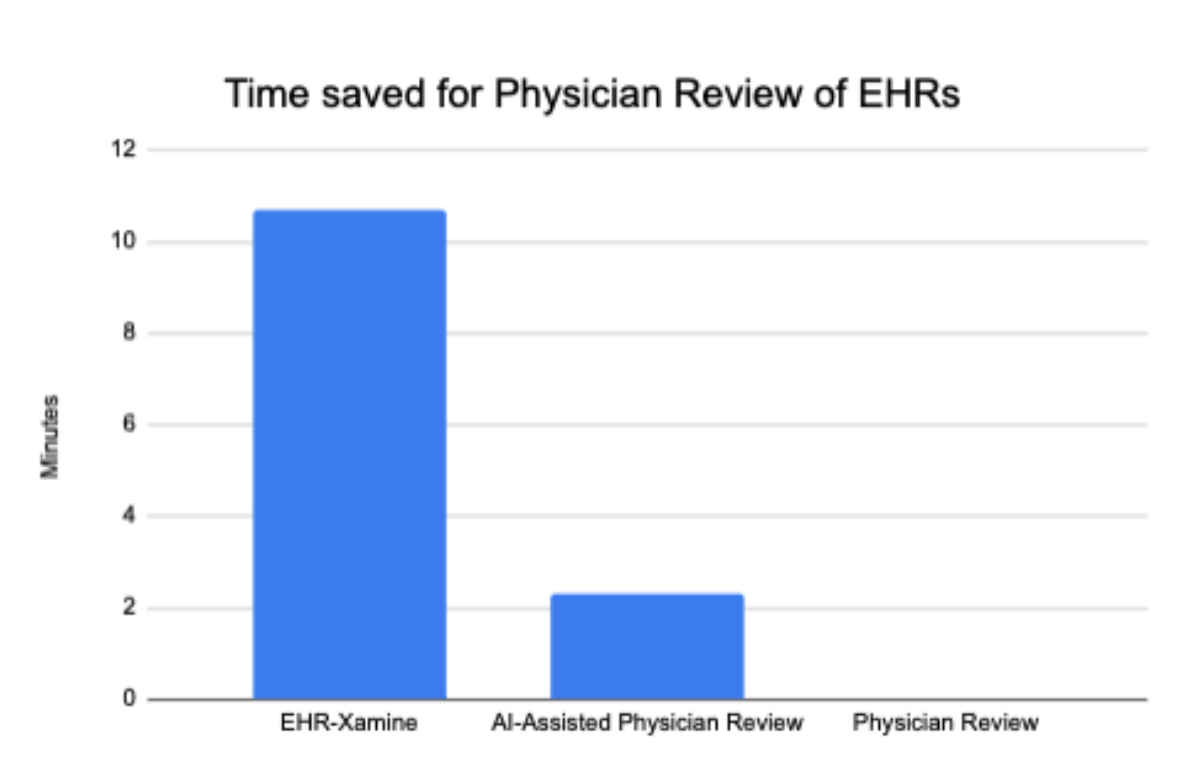

We believe that our model can impact the current healthcare system by saving many precious minutes in a physician’s EHR review of a patient. The time taken to answer all 23 questions per packet by EHR-Xamine was 1.8 minutes (95% CI: 1.5 - 2.1 minutes), with an average of 4.74 seconds per question. In comparison, physician review with AI-assisted packets took 10.5 minutes (95% CI, 8.5-12.6 minutes), while physician review without AI-assisted packets took 12.8 minutes (95% CI, 9.4-16.2 minutes), as seen in Figure 6. This represents an improvement of 83% time saved compared to AI-assisted packets, and 86% time saved compared to raw packets.

That being said, as our virtual assistant is designed as a tool for physicians, these statistics should be considered mainly as a baseline for the potential of EHR-Xamine in clinical trials. It’s inevitable that physicians will spend more time reviewing a packet, and perhaps in this process catch errors in both retrieval-type and counting-type questions that our current software makes. Nevertheless, the magnitude of time saved by the virtual assistant presents a strong case that our work is an improvement over Chi et al.’s proposed user interface.

Figure 6: Time saved (in minutes) by our EHR-Xamine virtual assistant in answering 23 relevant questions regarding a patient, compared to physicians using the AI-assisted software by Chi et al. [2] and physicians without any software.

Figure 6: Time saved (in minutes) by our EHR-Xamine virtual assistant in answering 23 relevant questions regarding a patient, compared to physicians using the AI-assisted software by Chi et al. [2] and physicians without any software.

Question Analysis

Across all twenty-three questions, all questions were answered correctly at least once across the four packets, and a total of twelve questions were answered correctly across all four packets, as seen in Table 2. Taking a deeper dive into the questions, we observe that aside from lab-related commands and two questions regarding a physician visit date and a patient insurance provider, all other questions are of yes/no format, suggesting that GPT-3 and the packet retrieval technology does best for questions that require a direct answer, especially questions that do not require any checking for duplicate information.

In comparison, only one question: How many gastroenterologist/hepatology office visit notes are there in the chart? was only answered correctly once across the four packets. Other poor-performing questions include Questions 1, 20 and 21 (How many endoscopies has the patient received?, When was the last gastroenterologist / hepatology office visit , and How many MRI of the abdomen of the pelvis reports are present? ); these are three of five questions that were only answered correctly exactly twice across the four packets. These questions suggest that not only are counting questions more difficult for our model to parse, but that the presence of medical terminology in a question prompted into GPT-3 may yield undesired outcomes.

Table 2: A list of all questions that EHR-Xamine answered correctly across all four times, across all four packets.

Table 2: A list of all questions that EHR-Xamine answered correctly across all four times, across all four packets.

Conclusion

This blog presents a novel virtual assistant that not only provides summaries of the patient and each individual packet within the document, but can also extract relevant patient information at more than five times the speed of physician while maintaining high accuracy. With the increasing concerns of burnout amongst physicians and rising hospitalization of citizens due to COVID and other illnesses, EHR-Xamine is the first of its kind to address these risks with a chatbot approach and scales extremely well with the amount of pages in a electronic health record (EHR) packet. Moreover, this paper proves that the implementation of large language models and GPT-3 in virtual assistants is feasible across scientific domains through a well-constructed pipeline and precise prompt engineering.

Footnotes

1 - I experimented with few shot prompting and it yielded better results, but due to GPT-3 credit restrictions I was unable to integrate it into the final pipeline.References

[1] Eunsoo H Park, Hannah I Watson, Felicity V Mehendale, and Alison Q O’Neil. Evaluating the impact on clinical task efficiency of a natural language processing algorithm for searching medical documents: Prospective crossover study. medRxiv, 2022.

[2] Ethan Andrew Chi, Gordon Chi, Cheuk To Tsui, Yan Jiang, Karolin Jarr, Chiraag V. Kulkarni, Michael Zhang, Jin Long, Andrew Y. Ng, Pranav Rajpurkar, and Sidhartha R. Sinha. Development and Validation of an Artificial Intelligence System to Optimize Clinician Review of Patient Records. JAMA Network Open, 4(7):e2117391–e2117391, 07 2021.

[3] Lin Ni, Chenhao Lu, Niu Liu, and Jiamou Liu. Mandy: Towards a smart primary care chatbot application. In Jian Chen, Thanaruk Theeramunkong, Thepachai Supnithi, and Xijin Tang, editors, Knowledge and Systems Sciences, pages 38–52, Singapore, 2017. Springer Singapore.

[4] Giovanni Campagna, Silei Xu, Mehrad Moradshahi, Richard Socher, and Monica S. Lam. Genie: A generator of natural language semantic parsers for virtual assistant commands. CoRR, abs/1904.09020, 2019.

[5] Mark Chen, Jerry Tworek, Heewoo Jun, Qiming Yuan, Henrique Ponde de Oliveira Pinto, Jared Kaplan, Harri Edwards, Yuri Burda, Nicholas Joseph, Greg Brockman, Alex Ray, Raul Puri, Gretchen Krueger, Michael Petrov, Heidy Khlaaf, Girish Sastry, Pamela Mishkin, Brooke Chan, Scott Gray, Nick Ryder, Mikhail Pavlov, Alethea Power, Lukasz Kaiser, Mohammad Bavarian, Clemens Winter, Philippe Tillet, Felipe Petroski Such, Dave Cummings, Matthias Plappert, Fotios Chantzis, Elizabeth Barnes, Ariel Herbert-Voss, William Hebgen Guss, Alex Nichol, Alex Paino, Nikolas Tezak, Jie Tang, Igor Babuschkin, Suchir Balaji, Shantanu Jain, William Saunders, Christopher Hesse, Andrew N. Carr, Jan Leike, Josh Achiam, Vedant Misra, Evan Morikawa, Alec Radford, Matthew Knight, Miles Brundage, Mira Murati, Katie Mayer, Peter Welinder, Bob McGrew, Dario Amodei, Sam McCandlish, Ilya Sutskever, and Wojciech Zaremba. Evaluating large language models trained on code, 2021.

[6] Ai copywriting amp; content generation for teams.

back